Compiled by Bruce Rickard

The author, Thomas Newkirk, writes about ‘owning the passages that speak to us.’ He says,

“We can learn to pay attention, concentrate, devote ourselves to authors. We can slow down so we can hear the voice of texts, feel the movement of sentences, experience the pleasure of words…and own passages that speak to us.”

Thomas Newkirk ‘The Art of Slow Reading’

My Book Notes are just that, ‘owning the passages that speak to me.’ By recording the words and sentences that capture my attention I am ensuring that they are not lost to me and will continue to challenge and inspire.

My Book Notes are not a summary of the text. I am not attempting to condense what the writer is wanting to communicate, nor am I providing an outline.

My Book Notes are not a review of the text. I am not analysing what has been written, nor am I making a comment.

I’m pleased to share with you My Book Notes and hope you might be motivated to consider reading the books for yourself. All the books listed have contributed to my thinking and enjoyment so come with my tick of approval.

Featured:

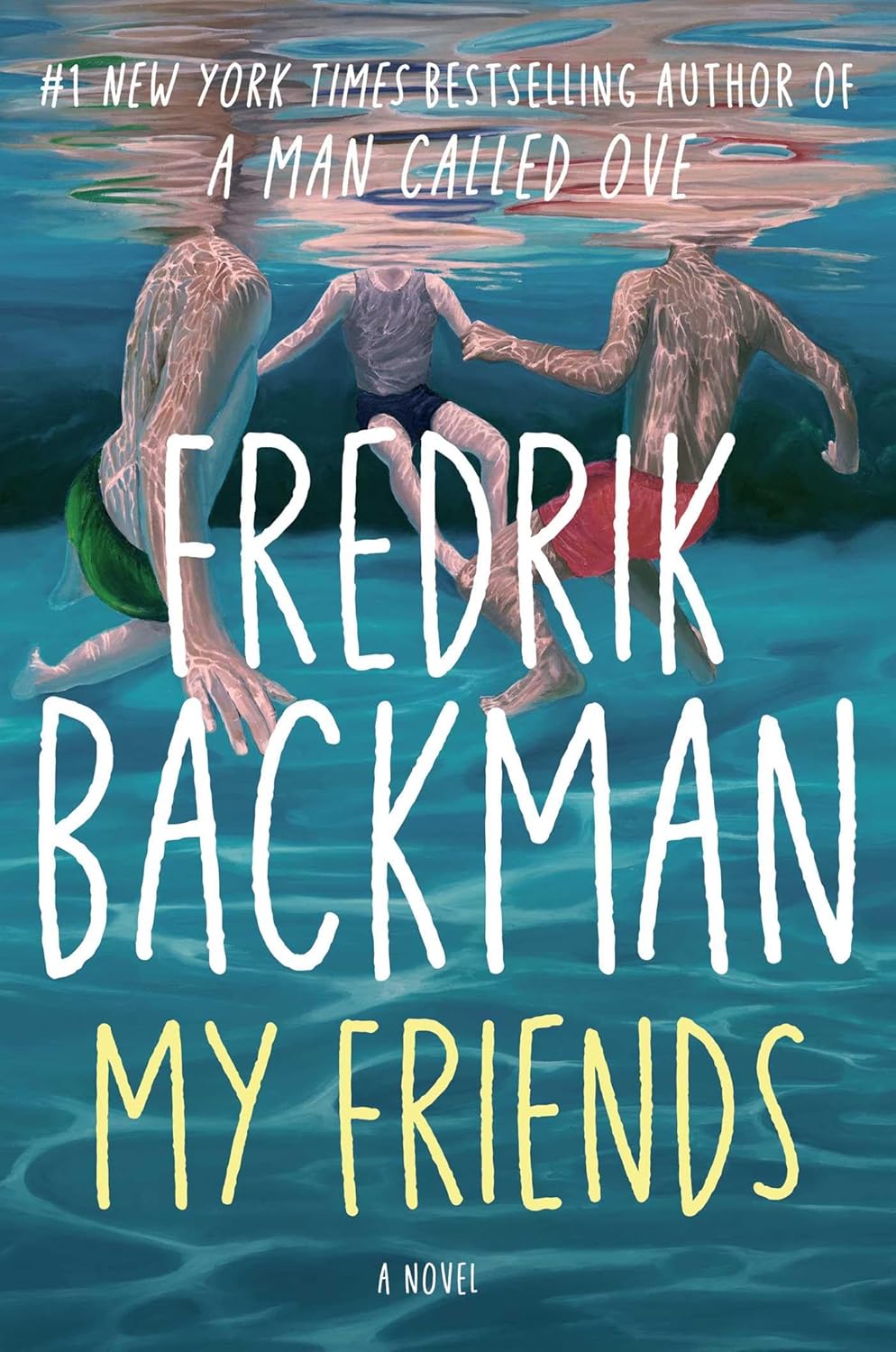

My Friends

Fredrik Backman

ISBN: 1398516406

Category: Fiction & Literature

Themes: Friendship, Loss, Stories, Sorrow, Abuse, Love, Art, Beauty, Hope, Death, Mourning, Memories, Truth, Love, Forgiveness

Date: January 2026

Rating: ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥

My Book Notes:

Fragile hearts break in palaces and in dark alleys alike.

* * * * * * *

There is a sort of happiness so overwhelming that it is almost unbearable, your soul seems to kick its way through your bones.

* * * * * * *

She races to the end of the block, then turns right, goes around a corner and thinks about the sea. She always does that when she is frightened, so she is thinking about the sea almost all the time.

* * * * * * *

[The older children]… are painted as if the artist saw them so intensively and dreamed them so beautifully that he learned how to whisper in colour. Painted by someone who must have been completely beaten to pieces inside, because no one could hold a brush so carefully otherwise, no one could paint friendship like this without first having been a completely lonely child.

* * * * * * *

Grown men don’t have enough things they are afraid of on this planet to become good at running.

* * * * * * *

Adults have never loved anything so much that it is worth being beaten up by a guard just to see it once in your life.

* * * * * * *

Life is long, his friend had said in the hospital, but he didn’t mention the fact that almost every moment hurts when you have to live it alone.

* * * * * * *

Art is chronological.

* * * * * * *

Nothing weighs more than someone else’s belief in you.

* * * * * * *

Grief is a selfish bacteria; it demands all our attention.

* * * * * * *

You don’t wish for happiness when you have lost the love of your life, because you can’t even imagine ever feeling happy again.

* * * * * * *

With the sort of friendship they had, there was never a before.

* * * * * * *

The only thing he (Joar) wasn’t much good at was being alone, because he hated silence, that was when he got all his worst ideas.

* * * * * * *

Everything the artist drew came from a place in his head that he could only get to if he wasn’t looking for it.

* * * * * * *

A lack of self-confidence is a devastating virus. There is no cure.

* * * * * * *

When they all laughed, they belonged together.

* * * * * * *

Grief is physical, an abuse of the living.

* * * * * * *

You think you are going to be young forever, but suddenly you reach an age where getting up from a chair can’t be taken for granted. It requires planning.

* * * * * * *

When you get old, gravity pulls the corners of your mouth down, the road to a smile grows longer.

* * * * * * *

The artist was an observer, he couldn’t bear to be observed, the world always gets those mixed up.

* * * * * * *

She (mother) wasn’t a bad person, I think, she was just… broken. Like some bits of her were missing, if you get what I mean.

* * * * * * *

The brain is so peculiar, the things that get stuck in it.

* * * * * * *

There is a difference from being loved and receiving love.

* * * * * * *

Art is what we leave of ourselves in other people.

* * * * * * *

The children of addicts always know what time it is.

* * * * * * *

A beautiful painting is the sum total of a person, what has happened to them, blessings and curses alike.

* * * * * * *

He replies slowly because the memories are coming in fits and starts, like water from a frozen pipe.

* * * * * * *

In the face of death grown men are like children, we think that if we close our eyes, we become invisible. We imagine that if we don’t open the newspaper, nothing terrible can have happened yet.

* * * * * * *

Art is a nakedness; you have to be free to decide when you’re comfortable with it and with whom.

* * * * * * *

Great art is a small break from human despair.

* * * * * * *

Adults never understand that for a child who uses drawing to escape from reality, being made to do it on command is unbearable.

* * * * * * *

No one can explain why some fourteen-year-olds want to die. Nature gains nothing from unhappy children, yet they are still walking around everywhere, without the words to describe their anxiety. Because how could you even begin to explain such a feeling to someone who has been happy and secure all their life?

* * * * * * *

Should you say it’s like a monster sleeping heavily on your lungs, so that every breath feels like your drowning? That it’s a voice in your head screaming that everything about you is a mistake.?

* * * * * * *

It doesn’t take any strength at all to crush someone’s self-confidence if you know where to stomp.

* * * * * * *

The most dangerous place on earth is inside us.

* * * * * * *

All parents feel the same: the days pass slowly but the year fly by.

* * * * * * *

Sometimes you don’t appreciate your own blessings until you see the envy in someone else.

* * * * * * *

Art needs friends, with our bodies against the wind and our hands cupped around the flame, until it’s strong enough to burn brightly with its own power.

* * * * * * *

You can’t love someone out of addiction; all the oceans are the tears of those who have tried.

* * * * * * *

What I hate most isn’t that people die; what I hate most is that they are dead. That I’m alive without them.

* * * * * * *

The world was too thorny for her; she kept getting scratched.

* * * * * * *

They wandered about in the sea of shelves between waves of books, and Louisa had never been in a quieter space.

* * * * * * *

The curse is the same for everyone who has loved someone who died of an overdose: we think that if we could just have been with our human every moment of every day, then it would never have happened. It never stops being our fault.

* * * * * * *

A bad foster home teaches a child a lot of things, but most of all to identify danger.

* * * * * * *

The most frightening thing about his dad dying the summer when he was fourteen wasn’t the grief he had felt, but the anger.

* * * * * * *

You can choose to be alone, but no-one chooses to be left.

* * * * * * *

Yet the most remarkable thing about losing a parent is that you don’t even need to miss them for their loss to be felt. The basic function of a parent is just to exist. You have to be there, like ballast in a boat, because otherwise your child capsizes.

* * * * * * *

People who have never been beaten up don’t understand the recklessness demanded of a person doing the beating, what must be missing from someone like that, or what happens inside the person being beaten.

* * * * * * *

Throughout our entire existence we have been on the run, first from wild animals, then from each other.

* * * * * * *

Grief is a luxury for those living an easier life.

* * * * * * *

They had no words, so they let him cry, only not alone.

* * * * * * *

Art is what can’t fit inside a person. The things that bubble over.

* * * * * * *

People say that anxiety is fear for no reason.

* * * * * * *

It is an act of violence when an adult yells at a child; all adults know that deep down, because all adults were once little.

* * * * * * *

Around here young men didn’t feel that they’d chosen a life, just that they had been allocated one. Life was an allotted period of time, like a prison sentence.

* * * * * * *

It’s hard to tell a story, any story, but it’s almost impossible if it’s your own.

* * * * * * *

Stories are complicated, memories are merciless, our brains only store a few moments from the best days of our lives, but we remember every second of the worst.

* * * * * * *

It’s exhausting to always be angry when you are a child, constantly having to tense your body not to cry, because you know that if you start, you will never be able to stop.

* * * * * * *

A violent man is a sickness for all around him. Violence is a plague that spreads through everybody it comes into contact with.

* * * * * * *

The good days were never good, they were a lie, then never lasted.

* * * * * * *

Life is long, but it moves at high speed, a single step here or there can be enough to ruin everything.

* * * * * * *

The world is full of miracles, but none greater than how far a young person can be carried by someone else’s belief in them.

* * * * * * *

Ted thought about how life is so fragile, coincidence decides so much, it takes so little to change everything.

* * * * * * *

It’s a funny thing. The person we fall in love with, we hardly ever call by their name. Because it’s somehow just so obvious that it’s you I’m talking to, that it’s you I’m always thinking of. Who else?

* * * * * * *

Disappointment is a powerful thing. Used correctly, it is stronger than fear, more terrible than physical pain, if you see it in the eyes of the one you love, you’ll do almost anything to make it stop.

* * * * * * *

When his eyes wandered from painting to painting, he looked like someone feeling sand between their toes for the first time or making their first snow angel.

* * * * * * *

People always say that you should live as if every day was our last, but when you have children, you realise that you have to live as if every day was their first.

* * * * * * *

Art doesn’t require training, dear child, art just needs friends.

* * * * * * *

That’s the worst thing about death, that it happens over and over again. That the human body can cry forever.

* * * * * * *

Getting stabbed with a knife is a trauma for the whole body; his leg was probably the part that healed quickest, it was the other parts of Ted what were limping.

* * * * * * *