Bibliotherapy is a therapeutic practice that uses books to nurture personal growth and improve mental health and wellbeing. The term ‘bibliotherapy’ is derived from a combination of two Greek words, biblion (meaning book) and therapeia (meaning healing).

In her book ‘Bibliotherapy: The Healing Power of Reading,’ Bijal Shah discusses the scope of bibliotherapy. She says,

‘Bibliotherapy can help individuals process emotions, gain new perspectives, and find solace in literature.’

Psychology Today explains how bibliotherapy works in a therapeutic setting: ‘Reading specific pieces of literature and talking about them with a therapist (or in a group therapy setting) is thought to help patients understand perspectives other than their own, make sense of a difficult past or upsetting symptoms, or experience feelings of hope, contentment, and empathy.’

Book therapy is not limited to a clinical setting. Reading books is advantageous for people of all ages, in any context. Reading is good for you.

John Cassian was a Christian monk and theologian, born in the 4th century. He subscribed to the conviction shared by so many monks and educators before him:

‘Reading was personally transformative. If you filled your life with the right kind of books, your perspective and behaviour would change.’

The transformative power of reading remains true today. Dr Juliane Roemhild, Senior Lecturer in English at La Trobe University discusses the benefits of reading. She says,

‘People read to alleviate stress and boredom, to find answers to life’s problems, for entertainment, for escape or company, to soothe, or to stimulate. Reading encourages us to reflect on our personal experience of life with the help of literature.’

Kathleen Mulhern is a scholar, an editor and author, a professor and speaker. She says,

‘By reading literature we learn to know ourselves in new ways. Literature can help us to have mercy on ourselves and others, can divest us of the ignorance that places ourselves at the centre of the universe, can make possible new ways of understanding our own befuddled choices.’

Examples of book therapy can be found in various works of fiction.

Tomoko and Takako are close friends and share a love of books. They are characters in Satoshi Yagisawa’s novel, More Days at the Morisaki Bookshop. For Takako, reading becomes a way to open herself up to the world, but for her friend Tomoko, literature is a consolation, and, at times, a retreat from the world.

Tomoko provides us with a personal example of book therapy. She says,

‘When I’m sad, I read. I can go on reading for hours. Reading quiets the turmoil I feel inside and brings me peace. Because when I’m immersed in the world of a book, no one can get hurt.’

Reading books can create a safe space, removed from the pain we are experiencing in the present. Reading books provides a form of respite, a chance to re-calibrate, to gain perspective, to find ourselves.

Thomas a Kempis, a Christian theologian in the 14th and 15th century knew the truth of these words. He says,

‘Everywhere I have sought peace and not found it, except in a corner with a book.’

Reading books can help us understand and process our grief:

When our son Adam took his life, I was desperate for answers. My world had been turned upside down. I was gasping for breath. I was hanging on, striving to comprehend the unfathomable. I needed to know that I hadn’t become detached from reality, that the confusion and trauma, the intense, heart wrenching grief were genuine.

The first book I read on suicide grief was After Suicide: Help for the Bereaved by Dr Sheila Clark. Published in 1995, the book offers practical commonsense and careful guidelines in navigating the challenges of suicide bereavement. It is not a technical book, but it does bring wisdom and perspective to the grief journey.

In the months following Adam’s death I experienced guilt feelings. I reasoned that I should have been more attentive, more understanding, more engaged. As a parent you feel responsible. I felt I had failed Adam.

Dr Sheila Clark addresses this issue. She says,

‘Guilt can be one of the most difficult and distressing emotions; you may feel guilty for not having been able to save your loved one from taking their life. With hindsight it is too easy to criticise what you have or have not done. Remember: You acted with the information you had at the time.’

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was an American poet and educator who lived in the 19th century. He wrote,

‘Take this sorrow to thy heart, and make it part of thee, and it shall nourish thee till thou art strong again.’

Rachel Joyce is an author who has sensitively addressed the complexity of suicide grief in a work of fiction. The novel, Maureen Fry and the Angel of the North, focusses on the immense sadness and loss experienced by Maureen when her only son David took his life. Joyce describes the devastating impact of David’s death on Maureen. She writes,

‘After David’s suicide thirty years ago, Maureen’s grief was so great she thought she would die of it. Really, she couldn’t understand how she was not dead. She wanted time to stop. Paralyse itself. But it didn’t. She had to get up every day and face his bedroom, the chair where he sat in the kitchen, his great big overcoat with no son inside it. Worse, she had to go out and face women and children, and young men who were high or drunk, and she had to walk past them without screaming.’

It took Maureen many years to acquire the courage to face her loss, to admit to her anger and bitterness, her jealousy, and her judgmental attitude. Maureen’s unwillingness to engage with her grief, to hide it away, denied people the opportunity to share in her pain, including her husband, Harold. We read,

‘Maureen had laid her deepest loss at the feet of the world and experienced nothing but an affirmation of her left-outness and her shame. David’s loss was her secret. It was the rock against which she was forever shattered.’

The term bereavement generally refers to the state of being deprived of something, but it is commonly used to describe a period of mourning related to the loss of a close relative or a friend.

To be ‘bereaved’ literally means ‘to be torn apart. When Adam died, I experienced overwhelming pain. My heart was broken. There was no way I could keep a lid on my grief. As Amanda Held Opelt suggests,

‘Grief goes where it wants with or without an invitation. It seeps into the empty spaces.’

My tears were not confined to private spaces. They heralded my pain in public places.

In his book The Wilderness of Suicide Grief, Alan D. Wolfelt PhD discusses what it means to integrate the grief that comes with a suicide death and why it is so important to honour your pain. He says,

‘Grief is not a disease. To be human means coming to know loss as part of your life… Being secretive with your emotions doesn’t integrate your painful feelings of loss; it complicates them. You cannot hide your feelings and find renewed meaning in your life.’

Reading books can help alleviate the loneliness we feel:

In the play Shadowlands, the character of C. S. Lewis says, ‘We read to know we are not alone.’

When we read, we develop an attachment with the characters. Madeline Martin, the author of The Librarian Spy notes that reading is a source of solace when our world is shaken. She writes,

‘The written word held such importance to her through the years. Books had been a solace in a world turned upside down, a connection to characters, when she was utterly alone, knowledge when she needed answers and so, so much more. In the war, they had given her insight, understanding, and appreciation. And even through letters and journals, words granted immortality for those whose stories she had been honoured to capture.’

Reading books can inspire hope even when we are fearful of the future:

Fear holds us captive. It weighs us down. It limits our potential. In his book The Winners Frederik Backman writes,

‘Fear turns some people into heroes but most of us only reveal our worst sides when we’re caught in its shadow.’

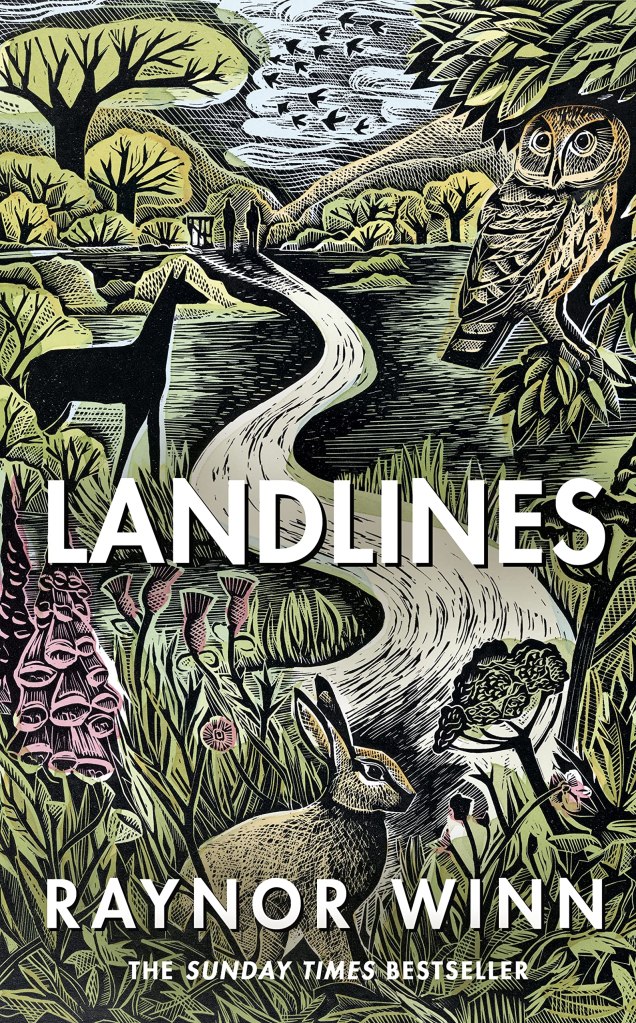

Hope on the other hand is liberating. It fills us with courage to live another day. In her book Landlines Raynor Winn chronicles her journey across Great Britain. It was a walk undertaken with her husband Moth. There were periods or weariness and discouragement and despair. At such times they needed reminding of the power of hope. They came across two mountain climbers who offered this encouragement.

‘We do the same thing every time we hang on a rope. We hope. Hope we will get to the top, hope the protection will hold, hope this will be the perfect climb. Hope. It is powerful; it can change things. But you have got to put yourself in the way of it, let yourself feel it. Let the power of it lift you up. That is what you are doing: putting yourself in the way of hope.’