The movie, The Boys in the Boat, based on Daniel James Brown’s New York Times best-seller of the same name, tells the remarkable true story of the University of Washington rowing team who competed for gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympic games.

During the recent coverage of the 2024 Paris Olympics, I observed that rowing crews who asserted their ascendency in the early stages of the race were often successful.

In the 1936 Berlin Olympics the U.S. eight-man crew defied the odds, completing a remarkable come from behind victory. The following dramatic account of the race, compiled by Lee Green J.D., captures the highly charged atmosphere that enveloped the six competing crews as they rowed for gold.

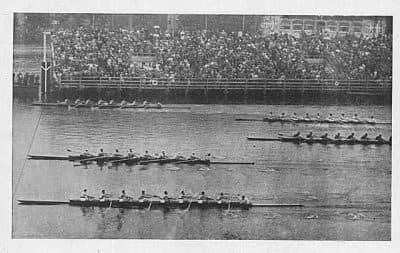

On August 14, 1936, in the Olympic eight-man finals, held on the Spree River in the Berlin suburb of Grunau in front of a crowd that included Adolph Hitler, Herman Goering and other Nazi officials, 75,000 German spectators, and a global radio audience estimated at 300 million, the U.S. shell was in last place out of six at the halfway mark of the 2,000-meter race.

The crew cranked its pace from the 32-strokes per minute it had averaged during the first half of the race to a theretofore-unheard-of 44-strokes per minute down the stretch, all the while maintaining perfect synchronicity.

With 200 meters to go, the U.S. passed Hungary; at the 100-meter mark Switzerland; and at the 50-meter line Great Britain. At the finish line, the U.S., Italy, and Germany appeared to be in a dead heat and for several minutes after the race, as the judges examined photographs of the finish, the crowd incessantly screamed “Deutschland, Deutschland.”

After a five-minute wait, the crowd quieted as the loudspeakers cackled to life for the announcement of the results: U.S. 6:25.4, Italy 6:26.0, and Germany 6:26.4. The US crew had won the gold medal by six-tenths of a second. Some commentators described the win as ‘the outstanding victory of the Olympic Games.’

The film version of The Boys in the Boat focuses on three inspirational figures that were pivotal to the crew’s success: Coach Al Ulbrickson, the boat’s number seven oarsman, Joe Rantz, and accomplished designer of rowing shells, George Yeoman Pocock.

The Coach:

Al Ulbrickson was 24 years old when he became the head coach for the University of Washington crew program following a decorated collegiate rowing career. His quiet, reserved manner had sportswriters calling him the “Dour Dane,” owing to his Nordic heritage and often solemn expression.

Because there was not much of an age gap between himself and the boys he was coaching, Ulbrickson felt he had to put on a stern, formidable exterior, to command their respect. He wanted to convey the sense that he was the boss. He dressed accordingly, making a habit of turning out at practice sessions in a business suit, necktie, and a fedora.

Coach Ulbrickson set an uncompromising standard from the start. No swearing, no smoking, no drinking was allowed. A solid academic standing needed to be maintained. And the team always came first.

Although success initially eluded him, Ulbrickson forged a culture of hard work and humility, of individual sacrifice and shared endeavour, which continues to this day.

Hard work implies sacrifice. It is putting aside your personal preferences and embracing the challenge, even if it involves suffering and hardship.

Ulbrickson mirrored hard work. He logged detailed observations on every training session in chemistry lab books, tracking and analysing performance data. He obsessed over stroke rates. He experimented with many different strategies and team combinations. He encouraged competitiveness, knowing what he wanted from them.

Ulbrickson was a demanding coach, driving his rowers to achieve more than they thought was possible. The boys who made up the successful Olympic crew spent many hours practicing in all types of weather. Over their career together they would race only 28 miles but row a total of 4,344 miles in practice sessions.

Humility is not a word we necessarily associate with rowing, particularly at the highest level. Ulbrickson thought it indispensable.

American novelist and short story writer, Flannery O’Connor, suggests that if we are to know our true self, we need to dispense with the swagger that says ‘I’ve got this. I know what I’m doing. I don’t need your help.’ She writes,

‘The first product of self-knowledge is humility.’

The word humble comes from the Latin words humilis and humus. To be down low. To be of the earth. To be on the ground.

Humility is knowing that you are a flawed human being with limitations, insecurities, and jealousies. Humility requires an act of surrender, trusting in the wisdom and knowledge offered to you, believing in the people you rely on. Humility is knowing that you cannot get there on your own.

Ulbrickson could see the potential in the current squad. The fundamental problem lay in their inability to work together. He says,

‘There were too many days when they rowed not as crews but as boatfuls of individuals. The more I scolded them for personal technical issues, even as I preached teamsmanship, the more the boys seemed to sink into their own separate and sometimes defiant little worlds.’

The greatest challenge Ulbrickson faced was to get his crew members to surrender their individuality and think and act collectively, to subsume their individual egos for the sake of the boat. They needed to understand that it was a shared endeavour. He had seen it and there was no denying it,

‘The most successful teams are the ones that row for each other.’

The Crew Member:

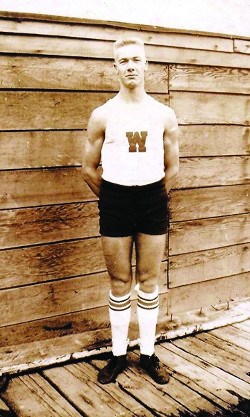

Joe Rantz was born March 31, 1914, in Spokane, Washington. His mother died when he was three and his father soon remarried. At age 10, despite being a good-natured, well-behaved boy who was a diligent student in school and who got along well with his four half-siblings, Joe was exiled from the family home by his stepmother, who took a dislike to him. He had to find ways to support himself while still a minor.

For more than a year, he slept in the town’s one-room schoolhouse which would be left unlocked at night. He exhibited extraordinary drive, determination, and ambition, foraging for food by fishing, hunting, and working odd jobs.

Joe Rantz was attending Roosevelt High School when the University of Washington rowing coach Al Ulbrickson stopped by looking for recruits for his team. He was impressed with Rantz’s strength in a gym class and left a card. He encouraged him to attend UW and try out for the crew team.

To realise his dream, Rantz had to work as a labourer for fifteen months after graduation to save the funds necessary to begin college. His financial situation remained a concern. He felt like everyone’s poor cousin. He wore his ragged sweater to practice every day, and the boys teased him continuously for it.

Rantz felt on the outer. His situation was precarious. He couldn’t afford to walk away, to fail. In his early life, he experienced betrayal and disappointment. He knew what it took to survive. He had trained himself not to rely on any other human being.

However, this challenge required a different approach. His independence was proving to be a liability. He was a talented athlete, but because of his hesitancy to befriend his teammates or form a bond of trust with them, he struggled to progress as a rower.

Rantz found a friend and mentor in George Pocock, the Washington team’s adviser, and a renowned boat maker. Pocock was a sensitive person who sympathised with Rantz’s working class anxieties and uncertainties. He encouraged him to let down his defences and trust his teammates. He said,

‘Joe, when you really start trusting those other boys, you will feel a power at work within you that is far beyond anything you have ever imagined. Sometimes, you will feel as if you have rowed right off the planet and are rowing among the stars.’

Joe Rantz had prodigious strength and unfailing determination. His presence in the boat inspired confidence. He was someone you could depend on in the heat of battle.

By the end of 1936, the University of Washington team was the best in the world: not just because of the individual rowers’ strength or form, but because all nine teammates had learned to work together.

Commenting on their success, coach Ulbrickson said,

‘Every man in the boat had absolute confidence in every one of his mates… Why they won cannot be attributed to an individual… Heartfelt cooperation all spring was responsible for the victory.’

The Craftsman:

George Yeoman Pocock was a descendent of accomplished boat makers in England. Pocock grew up learning about the subtleties of rowing and woodworking, and by the time he was twenty, had already become a highly accomplished designer of rowing shells.

After moving to the United States, Pocock became the world’s premier builder of rowing shells and throughout the 1930s, he was a key mentor and advisor on the University of Washington rowing team.

Pocock describes what it takes to design and build a world class rowing shell. He says,

‘You had to give yourself up to it spiritually; you had to surrender yourself absolutely to it. When you were done and walked away from the boat, you had to feel that you had left a piece of yourself behind in it forever, a bit of your heart… And a lot of life is like that too, the parts that really matter anyway.’

Pocock was well-liked by the crew and his wisdom and encouragement helped shape their thinking. When faced with conflict, he offered this timely advice.

‘The ability to yield, to bend, to give way, to accommodate,’ he said, ‘was sometimes a source of strength in men as well as in wood, so long as it was helmed by inner resolve and by principle.’

Pocock knew that muscle was never enough. It was vital that their hearts and minds were as one. It was then that they could draw on a source of strength outside of themselves. He says,

‘Men as fit as you, when your everyday strength is gone, can draw on a mysterious reservoir of power far greater. Then it is that you can reach for the stars. That is the way champions are made.’

Pocock encouraged the crew to strive for Harmony, Balance, and Rhythm. This is what he meant by rhythm.

‘When you get the rhythm in an eight, it is pure pleasure. It is called ‘swing,’ rowing in such perfect unison that not a single action is out of sync. Good swing feels like poetry.’

This is a story about values that sustain a culture of success. The values embodied by the boys in the boat and those who supported them served them well. Values such as HARD WORK, COMMITMENT, SACRIFICE, SUFFERING, DETERMINATION, TEAMWORK, HUMILITY, SELFLESSNESS, PERSEVERANCE, TRUST, BELIEF.

These are the values that society needs to rediscover. These are the values that will sustain us throughout our days. These are the values that guarantee our ultimate success.