Parker J Palmer was born in Chicago on February 28, 1939, and grew up in Wilmette and Kenilworth, Illinois.

Palmer is a world-renowned writer, speaker, activist, and Quaker elder who focuses on issues in education, community, leadership, spirituality, and social change. He is founder and Senior Partner Emeritus of the Centre for Courage & Renewal.

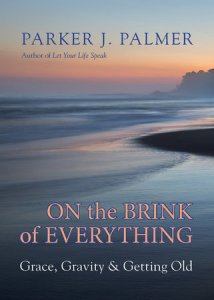

Palmer is the author of ten books – including several award-winning titles – that have sold two million copies and been translated into ten languages. His latest book, On the Brink of Everything, was published in 2018. It is a meditation on a life spanning eight decades. He says,

‘This book, my tenth, is one fruit of my collaboration with aging — an offering from a fellow traveller to those who share this road, pondering as they go.’

Writing is one of the ways Palmer collaborates with life. His writing is not prescriptive, but ‘an unfolding of what is going on inside me as I talk to myself on a pad of paper or a computer.’

Palmer writes with clarity and purpose. His honesty allows the reader to see the struggle, to appreciate the wisdom, to know that what is given is the product of courage and perseverance and a large measure of humility.

As an educator, Palmer values discovery. Nothing of value falls into our lap. It must be sought relentlessly, dismissing every distraction, focussed on the prize. He says,

‘Paths that lead to meaning have to be hacked out of complexity and confusion.’

On the Brink of Everything sheds light on seven distinct themes that bring meaning to life.

Sacred:

The sacred is that which is highly valued and important due to its connection with God and is deserving of profound respect and reverence.

In 1974, Parker J Palmer left his community organising job in Washington, DC, and moved with his family to a Quaker living-learning community called Pendle Hill, located near Philadelphia. For the next eleven years, he shared a daily round of worship, study, work, social outreach, and communal meals with some seventy people in a spiritually grounded community.

In this structured environment he discovered afresh ‘the sacredness of the ordinary.’ It is the sacred that gives value and meaning to every aspect of our existence. When we acknowledge the sacred, life is precious, but without it, life is pitiful.

Those who embrace the secularisation of society argue that the sacred is outdated and irrelevant. They do not see that self-seeking ideologies have no substance, that without the sacred there are no restraints, and their world will crumble and fall.

If life is sacred, then what we do really matters. Quaker tradition emphasises silence, for it is in the silence that we await the filling of the Holy Spirit. The presence of the Holy Spirit in our life inspires our worship and ignites our service.

Palmer discovered that ‘silence is sacred.’ It is where he encountered God, and it was His presence in his life that shaped his passion for social action. He says,

‘In the Quaker tradition I found a way to join the inner journey with social concerns, which later led me to establish the Centre for Courage and Renewal, an international nonprofit whose mission is to help people in various walks of life ‘rejoin soul and role.’

Survival:

Our commitment to the sacred will be tested. Whenever we place a value on something we must ask ourselves, ‘How much do I value this thing – this friendship, this job, this membership, this commitment?’

The sacred is hidden or obscured when our life is under threat, and our survival compromised.

Parker J Palmer experienced three major bouts of depression, the first when he was in his forties. He says,

‘My faith has been challenged by experiences of failure and experiences of clinical depression; times of deep darkness when I was not sure it was worth living anymore… While you are down there, reality disappears. Everything is illusion fostered on you by the self-destructive ‘voice of depression,’ the voice that keeps telling you, you are a waste of space, the world is a torture chamber, and nothing short of death can give you peace.’

Clinical depression can be managed. Palmer sought counselling to understand the causes for his loss of self and the triggers that plunged him into darkness. He took the prescribed antidepressants knowing that he needed to get ‘some ground under his feet.’

The sacred is worth fighting for. When you stumble in the dark you still have ‘a semblance of self that you can use to try to navigate and negotiate and grope your way towards some light.’ Our survival is dependent on reminding ourselves of what it is we want, the treasures of everyday realities – ‘a crimson glow on the horizon, a friend’s love, a stranger’s kindness, another precious day of life.’

Suffering:

Suffering is a part of life. Suffering breaks our hearts. Parker J Palmer provides the context. He says,

‘Heartbreak comes with the territory called being human. When love and trust fail us, when what once brought meaning goes dry, when a dream drifts out of reach, when a devastating disease strikes, or when someone precious to us dies, our hearts break and we suffer.’

Palmer stresses the need to consider what we do with our pain. He says,

‘Sometimes we try to numb the pain of suffering in ways that dishonour our souls. We turn to noise, frenzy, nonstop work, and substance abuse as anaesthetics that only deepen our suffering.’

Palmer suggests that suffering can be transformed into something that brings life, not death. The outcome is determined by the way our heart breaks. He says,

‘The brittle heart breaks into shards, shattering the one who suffers as it explodes, and sometimes taking others down when it is thrown like a grenade at the ostensible source of its pain.’

The supple heart is something else. It breaks open, not apart, allowing for growth toward completeness. He says,

‘Only the supple heart can hold suffering in a way that opens to new life. We can make our hearts more supple by stretching them, the way a runner stretches the leg muscles to avoid injury.’

Simplicity:

Modern living embraces ‘a culture of excess.’ We accept that more is better. Acquisitions mirror our prosperity. Possessions reflect our values and what motivates us. Everything about modern culture involves complexity and unnecessary layers.

The accumulation of clutter detracts from our quality of life impeding our ability to focus, relax, and connect with what truly matters. It can leave us feeling stressed and overwhelmed if it gets to be too much or interferes with our ability to function effectively.

We find it difficult to divest ourselves of stuff. We form attachments to things. Our reluctance to let go is often for obtuse or sentimental reasons.

Influential Russian author Leo Tolstoy says,

‘There is no greatness where there is not simplicity, goodness, and truth.’

Simplicity is about identifying what is essential and eliminating the rest. Parker J Palmer laments our sell out to complexity. He says,

‘We are pulled towards rare and hard-to-follow ideas; we entertain our friends with elaborate meals; we pursue convoluted relationships; we have careers that enmesh us in cumbersome commitments; we fill our leisure hours with exotic hobbies…’

Simplicity is the treasure we desire, but it takes courage to pursue it. Palmer says,

‘It can take a very long time indeed to work up the courage to be simple: to read simple books, to wear simple clothes, to have simple days and to say simple things.’

The beauty of simplicity lies in its power to transform both our external world and our internal landscape.

Solitude:

Solitude is not about the absence of other people – it is about being fully present to ourselves. This is the great paradox, our need for solitude and community. Parker J Palmer warns of the danger of choosing one over the other. He says,

‘Solitude split off from community is no longer a rich and fulfilling experience of inwardness; now it becomes loneliness, a terrible isolation. Community split off from solitude is no longer a nurturing network of relationships; now it becomes a crowd, an alienating buzz of too many people and too much noise.’

Palmer found solitude in nature. Immersing himself in nature brought clarity to his mind and peace to his soul. He says,

‘There is nothing like a walk in the woods, into the mountains, alongside the ocean, or out in the desert to put my life in perspective.’

Palmer saw value in spending time alone, distancing himself from the turmoil of modern living. He sought out quiet, unhurried spaces where he could rest in God’s presence and experience times of refreshing and spiritual renewal. He writes about one such experience. He says,

‘After five days of silence and solitude, I am noticing that many of the demands that hung over me when I came out here have lightened or wafted away. Since I have done little this week to meet those demands, the lesson seems clear; they were mostly the inventions of an agitated mind. Not that my mind has quieted, its tyranny has been undermined, and I feel more at peace.’

Author Henri Nouwen says,

‘In solitude we discover that being is more important than having, and that we are worth more than the results of our efforts.’

Service:

Parker J Palmer is a Quaker. He stands in a religious tradition that asks him to live by such values as community, equality, simplicity, and non-violence.

Palmer found inspiration for a life of sacrifice and service in nature. He says,

‘Nature constantly reminds me that everything has a place, that nothing need be excluded. Wholeness is the goal, but wholeness does not mean perfection. It means embracing brokenness as an integral part of life.’

Palmer has a great deal to say about brokenness. It is at the heart of Christian life and service. It suggests paradox – life from death; hope from despair; success from failure. He says,

‘To grow in love and service, you must value ignorance as much as knowledge and failure as much as success.’

Palmer reminds us that if we want to serve God faithfully and gracefully, it must flow from a broken-open heart. A broken-open heart knows no malice or hatred but seeks love, truth, and justice. He says,

‘The broken-open heart is a place of spiritual alchemy, where the dross of hard experience can be transformed into the gold of wisdom.’

Sanctuary:

Parker J Palmer talks about the volatility of our world, about the disrespectful forces that pick us up and throw us about. Palmer suggests that the only way to manage this disruption, this assault on our souls, is to seek sanctuary. He says,

‘Seeking Sanctuary is about finding the solace and support we need when our engagement with the rough-and-tumble of political exchanges and vigorous debate starts to cost us our physical and mental well-being.’

Sanctuary is front and centre in his thinking and acting. It is his coping strategy. It allows him to press on, to be strong. Sanctuary exists in the more obvious places. It also comes unexpectedly. He says,

‘Sanctuary is as vital as breathing to me. Sometimes I find it in churches, monasteries, and other sites formerly designated ‘sacred.’ But more often I find it in places sacred to my soul: in the natural world, in the company of a faithful friend, in solitary or shared silence, in the ambience of a good poem or good music.’

Sanctuary guarantees our spiritual survival. Without it we are a spent force. Palmer concludes,