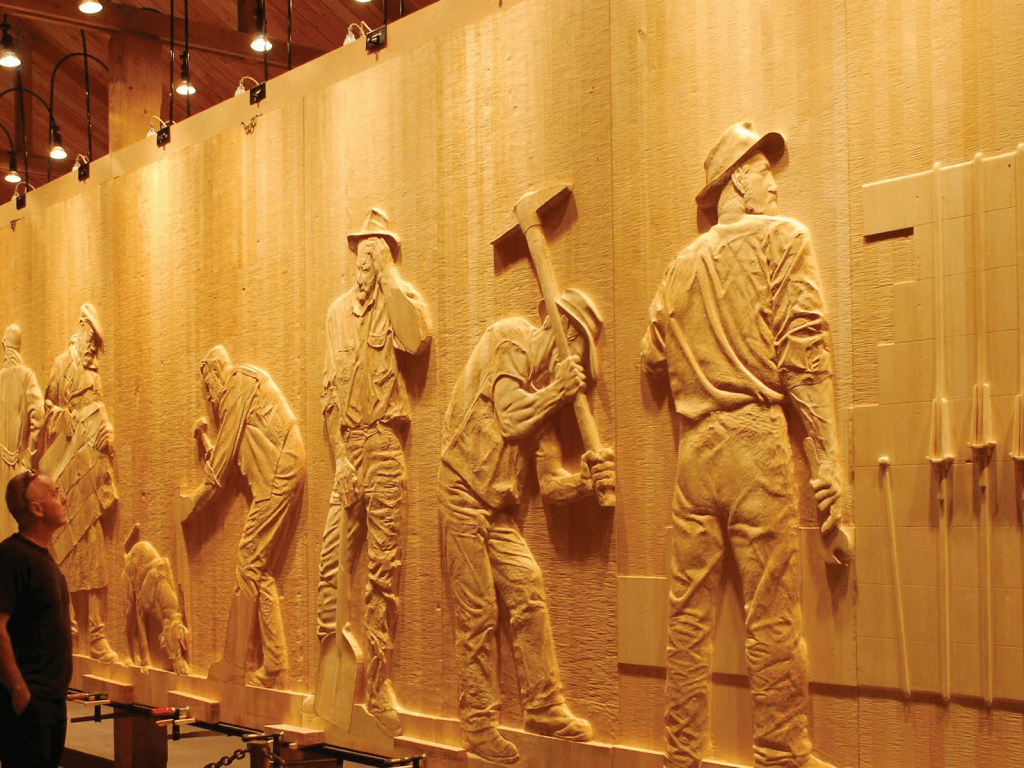

We recently visited ‘The Wall’ in the central highlands of Tasmania. The location of The Wall is remote, off the beaten track. It is marketed as ‘The Wall in the Wilderness.’

The creator/designer, Greg Duncan, sculptured The Wall out of Huon Pine. It stands three metres high and is over one hundred metres in length. It represents a decade of, at times, arduous work.

Discovery Tasmania describes The Wall and its importance.

‘The beautifully carved works set out in relief sculpture depict the history, hardship and perseverance of the people in the Central Highlands and pay homage to the individuals who settled and protected Tasmania.’

The Wall evokes a raft of emotions. There is awe and wonder, the size and magnificence of the work is breathtaking. There is sadness and grief, the sensitive depictions of life highlighting the challenges earlier generations met – the struggle to survive, to create a sustainable existence, to build a future.

Some of the panels are partially complete, highlighting the process. It is unsettling. Like an unfinished symphony, it leaves you feeling unfulfilled, hungering resolution, longing for completion.

Endings are important. They allow us to breathe, to move on. Otherwise, we are left in a state of tension, confused, uncertain. How something ends colours how we view what goes before.

I can understand why an artist may want us to know how he achieved the smooth folds and fine detail. A short video of him working on the project would have sufficed.

But the unfinished work may have something else to say. The past can never be represented perfectly. Artists and historians are the masters of adaption. The stories they tell are shaped by their understanding, beliefs, and prejudices. No matter the credentials of the storyteller the story is never the whole story. It is but a small part of a larger canvas.

The Wall reminds us that the past informs and inspires us, that there is beauty in hardship, that despite the struggle and shattered dreams there is hope.

In her memoir ‘Unfinished Woman’ author Robyn Davidson attempts to make sense of the past, ‘a curtain drawn aside to reveal the theatre of life as it exists inside my mind and no one else’s.’

Davidson was eleven years old when her mother hanged herself from the rafters of the garage. As Davidson says,

‘The consequences of her death play out in a million ways.’

One reviewer suggests that the title of the book, ‘Unfinished Woman,’ not only describes the author, but is a fitting description of her mother as well.

Davidson’s mother was forty-six when she died. Davidson speaks candidly about her feelings. She says,

‘I do not feel any emotion when I think of my mother’s death. I have imagined the act, what it required to do it, but I imagine it as one sees a scene in a film. It holds no special significance for me. Perhaps by the time she killed herself I was already quite far away. In any case, when I touch the area around that day, I can feel only callous.’

Davidson had never considered writing about her mother, that is until she approached the same age she died. She says,

‘Then that erased, safely buried woman came back with, literally a vengeance. It was as if she were imprecating me to release her from the prison of other people’s stories. It was my duty to do so. There was no one else who would or could. She had been misrepresented, dishonoured, murdered.’

It is an onerous responsibility to honour the remembrance of a loved one, to record what you remember, to interpret what you observed, to attach meaning to what does not make sense. Finding the right words, the right tone, takes courage and imagination. It is a re-construction, putting the disparate pieces together.

I am writing about my son Adam. He died thirteen years ago. He took his life. I have made several attempts at drafting a book about him previously, but I was never satisfied with the format, knowing precisely where to start. Telling his life story in linear fashion did not work.

Our memories are not filed systematically. They look more like a scrapbook, indiscriminate pages torn from a life, stained, crinkled, with ragged edges.

Davidson has a great deal to say about memories. She says,

‘The way memory plays in the mind is not factual. It is sketchy, mythical, misremembered, contradictory. It is flickers of light on unfathomable darkness. We go back over and back over the past, watching it change with each take, not thinking of it as what happened so much as, what does it mean? What do we say about it, and what do we choose not to say?’

Davidson suggests we are left to interpret what we have been given, that memories are released from a hidden vault when we are ready to receive them, to embrace them, to learn from them. Sitting quietly with our memories allows them to say what they want to say, reveal what the want to reveal. They have their own voice.

Davidson is the sort of person who lives her life forward. She is happy to leave the past in the past, to not allow the past to diminish her curiosity in the future. She says,

‘I had used a kind of scorched-earth policy regarding my past. I threw bombs over my shoulder, and seeds ahead of me, into the future, on the assumption that when I arrived there, something would be growing.’

On her return to Australia Davidson discovers that there are few physical reminders of her mother. She says,

‘A serviette ring my father had made for her, an inscription in a Bible she gave me, a few notes scribbled in a little memo book regarding the Mooloolah School of Arts ‘concert.’ There were no letters. Her clothes and jewellery had been dispersed. Her old ball gowns, those treasures of my childhood, burnt.’

The nature of her death forced the family to erase her from their consciousness. Buried grief does that. Where there is guilt and shame there is an attempt to conceal, to remove anything that might trigger an emotional response.

Davidson recognises that if she is to write about her mother, inspiration will not come from out there but from within. She says,

‘I came to terms with the fact that my mother could not, could never, be found, that the only wisps remaining of her tiny moment on earth were encoded in me…’

Davidson identifies some of the factors that led to her mother’s suicide. It is complex. Loneliness is unavoidable. For some it is a fertile thing, inspiring productive endeavours. For others, loneliness is intolerable, a captive existence, denying them the space to breathe. Regarding her mother, Davidson says,

‘The loneliness outside of marriage was hard to bear, but loneliness inside the marriage wounded and diminished her.’

Davidson’s mother is a city woman, cultured, ‘neat and careful with her appearance.’ She reigns over the inside of the house, working tirelessly, cooking, cleaning, sewing her daughters’ clothes on a treadle Singer sewing machine, teaching her oldest daughter correspondence school. She enjoys reading and listens to the Sunday evening plays from the BBC.

Davidson’s father is at home outside, in nature. He is hard working, but tight with the purse strings. He expects his wife to be subordinate, unquestioning, compliant. He does not affirm her contribution to family life and denies her small ‘extravagances’ that will feed her soul. She must adapt, conform, embrace an impoverished way of living, make sacrifices, cope with the isolation, manage her fear of snakes.

Over time Davidson’s mother, who is small in stature, is worn down both physically and emotionally. She feels desolate, no longer respected, appreciated, or needed. She can see no way out, no alternate pathway, no future.

Some people imagine suicide to be the coward’s way out, a betrayal, a reneging of commitments, an abandonment of those they love.

Some people see suicide as an unfinished life, a life cut short, a life lacking resolution, a life that has failed to realise its potential.

But an unfinished life is nothing more than a life that is misunderstood. Davidson wanted to address the confusion surrounding her mother’s life. She honoured her mother by making her known. I want to do the same for my son.

In 1977, then 27-year-old Robyn Davidson set out on a solo camel trak across Australia’s harsh and unforgiving interior. In her memoir, Tracks, Davidson retraces her journey. My Blog Post, Surviving the Desert, reflects on this experience.