Book burning predates the time of Christ. However, prior to the printing press the ritual destruction of books by fire was less common. Handprinted manuscripts were valuable for their scarcity and few people had access to them.

The great bonfires of May 10, 1933, in Berlin, are regarded as the most famous book burning in history. The Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels was determined to eliminate any Jewish or otherwise ‘objectionable’ influence from the cultural life of Germany.

Nazis and students burn books on a huge bonfire of ‘anti-German’ literature in Opernplatz, Berlin, in 1933. Keystone/Getty Images

Readers of Mein Kampf (My Struggle) might recall the words of the author, Adolf Hitler.

‘A smart reader should take away from books only the ideas that support their own beliefs and discard the rest as useless ballast.’

An abridged quote taken from the original text.

Germany’s history of burning books did not start with the Nazis. In 1817, for the 300th anniversary of Martin Luther’s launching of Protestantism, students, demonstrating for a unified country, held a major burning of antinational and reactionary texts and literature which they viewed as ‘un-German.’

In 1933, it was the university students who again were at the forefront. Urged on by Goebbels, they created backlists of works by literary and political figures such as Thomas Mann, Erich Maria Remarque, Ernest Hemingway, and Helen Keller that were thrown into the flames.

- The 1929 Nobel Prize-winning German author Thomas Mann is rejected for his support of the Weimar Republic and his critique of fascism.

- Erich Maria Remarque is out of favour for his unflinching description of war in All Quiet on the Western Front.

- The American author Ernest Hemingway is considered a corrupting foreign influence.

- The American author, Helen Keller is banned for her commitment to social justice, and her support of disabled people, pacifism, improved conditions for industrial workers, and women’s voting rights.

The book burnings took place in thirty-four university towns and cities. Works of prominent Jewish, liberal, and leftist writers ended up in the bonfires. The book burnings stood as a powerful symbol of Nazi intolerance and censorship. Nazi authorities were out to close off society to certain ideas.

Speaking to an enthusiastic crowd on the night of the burnings, Joseph Goebbels says,

‘The old goes up in flames, the new shall be fashioned from the flame in our hearts.’

Ironically, the Nazis had trouble keeping the fires lit. A light rain was falling. They had to pour gasoline on the stacks of books.

In the aftermath of the book burnings the Nazi regime raided bookstores, libraries, and publishers’ warehouses to confiscate materials it deemed dangerous.

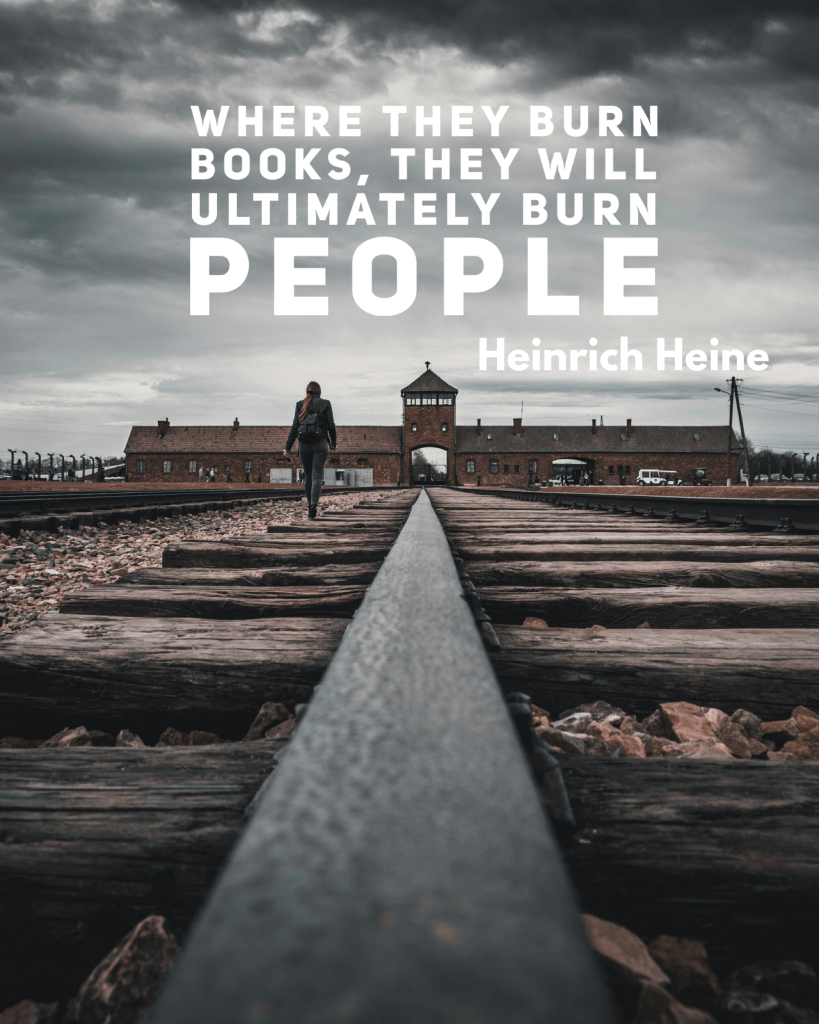

It is sobering to contemplate that beloved nineteenth-century German Jewish poet Heinrich Heine, wrote in his 1820-1821 play Almansor the famous admonition,

‘Where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people.’

In her historical novel The Librarian of Burned Books, author Brianna Labuskes describes the burnings and their aftermath through the eyes of Hannah, a resident of Berlin. Hannah says,

‘The fires did not simply last one night… The night of May tenth was the grand demonstration, but Germans were encouraged to burn their own personal collections in the weeks after. Anything that was considered anti-German or that might undermine the Reich had to be purged.’

Hannah continues,

‘That is, anything written by Jewish authors, communists and deviants and anyone not espousing the greatness of the master race.’

Hannah is a guardian of books. After leaving Germany she found a job at The Library of Burned Books, in Montparnasse, on the left bank of the Seine. The library exists to preserve books the Nazis sought to destroy. Hannah is convinced that burning books will never erase their value. Books live on in the hearts of the reader. Their importance in shaping who we are cannot be underestimated. She says,

‘Books are a way we leave a mark on the world. They say we were here, we loved, and we grieved, and we laughed, and we made mistakes, and we existed. They can be burned halfway across the world, but the words cannot be unread, the stories cannot be untold.’

Hannah’s words speak to our time. We want the world to only think as we think. We strive to silence the voices with which we do not agree. We despise the wisdom that has guarded and sustained previous generations. We devise strategies to erase the memory of celebrated individuals whose achievements we dismiss as misguided, destructive, or hurtful. Hannah is convinced that…

- Words cannot be unwritten simply because you burn them.

- Ideas cannot simply be erased.

- People cannot be erased.

- Burning books about things you do not like or understand does not mean those things no longer exist.

Later in life, Hannah is invited to speak to an American audience about censorship, banning access to books that offer a different way of seeing things. Hannah draws on her life experience. She says,

‘There are nights I lie awake wondering what the moment was that we lost the Germany I knew, a country that prized intellectualism, reason, and civil discourse, a country that held a reverence for books. Some might point to the invasion of Poland, some Kristallnacht, the Night of the Long Knives, the Jewish boycotts, the race laws, the opening of the concentration camps, the November treaty that brought about so much bitterness. I think it was the moment right before the gasoline was poured on the books. The moment the most educated country in the world willingly, joyously, wholeheartedly turned away from knowledge.’

Andrew Pettegree, a Professor of History at St Andrews University, offers a cautionary word, reminding us that it is foolish to assume ‘that books are invariably a force for good: a civilising influence to be cherished and preserved.’ Some books have evil intent, ‘incubating the ideologies that set nations against each other and perpetuating the stereotypes that lead to atrocities and genocide.’ He says,

‘Books are never above the fray; they reflect the human frailties and evil intent of those who go to war, even as reading provides a haven of peace.’

In 1953, Ray Bradbury’s futuristic novel Fahrenheit 451 was published. The novel foresees a time when books will not only be banned but anyone in possession of them will be punished and the books destroyed. It is ironic that a book that highlights our unwillingness to listen to the truth has been banned periodically. Any society that believes keeping the truth from people will keep them safe is in danger of imploding.

The leading character in Fahrenheit 451 is a firefighter named Guy Montag. Firefighters have been re-assigned. They no longer put out fires but rather start them. They uphold the law, and the law states ‘no-one is to be in possession of a book.’ Guilty parties are punished, their houses destroyed, and their books burned.

The defining moment comes when Montag and his colleagues encounter an elderly woman who would rather burn with her books than live without them. During the resultant mayhem Montag grabs a book and hides it under his coat. He later realises that the book he has rescued is a Bible.

Montag’s subversive actions place him at risk, and he is forced to flee the city. He is pursued by the authorities who are desperate to demonstrate that his crime of independent thinking cannot and will not go unpunished.

Montag seeks out an old Professor, a supporter of learning, an educator. Professor Faber reminds Montag that rescuing books is commendable, but it is ‘the detailed awareness of life they contain’ that must be valued and preserved. Proffering ignorance over knowledge is no way to create a just society. He says,

‘Those who don’t build must burn.’

Faber helps Montag escape to the countryside, where he comes across a group of renegade intellectuals (“the Book People”), led by a man named Granger, who welcome him. They are the guardians of truth, and are part of a nationwide network of book lovers who have memorised many great works of literature and philosophy – Charles Darwin, Bertrand Russell, Jonathon Swift, Einstein, Schweitzer, Ghandi, Jefferson, Byron, Thoreau, and Christ – to name a few. They hope to keep the knowledge that will be invaluable to future generations, intact and safe. They say,

‘The books are waiting, with their pages uncut, for the customers who might come by in later years, some with clean and some with dirty fingers.’

Montag’s role is to memorise the Book of Ecclesiastes, a book that reminds us that when we remove God from our lives all else is ‘chasing after the wind.’ There are also words to inspire hope in times of uncertainty and turmoil.